The Probabilistic Nature of our World

When one starts learning about physics in secondary school and junior college (high school), one starts off with the classical Newtonian physics. This is excellent to develop intuition for the young minds. Newtonian physics can be boiled down to the three laws of motion proposed by Newton. Thus, if we were given the initial velocity and location of an object(s) and the forces acting on them, we can quickly calculate the future velocity and location of the object(s).

This deterministic world is what we are used to. When we apply force on an object, we expect it to do something. For example: we push a door, we expect it to open. As Einstein put it, “God does not play dice with the universe.” For the longest time, I used to be happy with the deterministic world and there was no reason to be unhappy because all my problems were in a world where my Newtonian physics worked. As a Mechanical Engineer, I wasn’t dealing with objects traveling at or approaching the speed of light. Neither was I looking into the quantum realm. I was looking at the macroscopic world of fluid dynamics: flow around wings, balls, and other objects. Moreover, I was solving problems in the deterministic region of laminar flows.

As my interest in fluid dynamics grew, I came across my first encounter with randomness and chaos- turbulence. Through conversations with various seniors, I was made to be afraid of two things in fluid dynamics: compressible flows and turbulent flows. Why? Because they were extremely difficult to grasp. I knew no better. Turbulence was chaos on a grand scale as everything I knew about flows would breakdown: the flow was no longer constant (there were wiggles in the velocity), there was mixing of flow, there were new terms which made no sense (eddy diffusivity, turbulent kinetic energy).

It took me a good part of 2 years to accept the fact that our world is in fact a world of probabilities. It’s just that before encountering this, I was working with problems where the fluctuations were of the order $latex 10^{-19}$. Dr. Ramamurti Shankar’s class on Quantum Mechanics uploaded on Yale’s YouTube page gave me the necessary confidence to look at my so-called deterministic world and accept it as being a world full of probabilities.

Once we drop the requirement for everything to be deterministic, we come across a world of problems where we can provide only estimates, but can never be 100% certain. A problem I was recently discussing with a friend involved random walks.

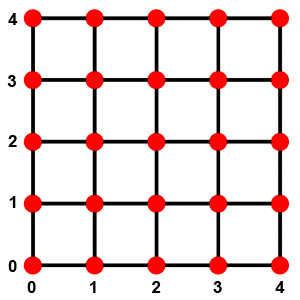

Random walk is a classical computer science problem where you are at the origin and are asked to move a set number of step on a grid. In a more abstract sense, the random walk problem can help you explore all the possible scenario you could encounter given the number of steps.

|

Consider the grid here. Let us define the axes in the usual sense. You are at (0,0). Now, I ask you the following: find me the number of way to get to (1,1) in 2 steps.

Let’s explore how you can make it to (1,1) form (0,0).

i. You take the first step towards (1,0) and the next step towards (1,1).

ii. You take the first step towards (0,1) and the next step towards (1,1).

These are the only two possibilties.

Now, if I leave you on the grid and stop observing, can I know which path you took to get to (1,1) with 100% certainty? Absolutely not. But I can say that since you took only two steps and are (1,1), you only had two possible paths and you had a 50-50 chance of taking either path.

Even though you are certainly at (1,1) in a deterministic manner (there is no question about that because I see you there), I am uncertain about the path you took and can never be certain unless I observed you. This, loosely, is how the quantum realm works.

Moving from quantum mechanics, and looking at the chaotic world of turbulence, a similar argument can be presented. Let us consider a simple turbulent flow in a pipe. In the laminar sense, this flow would form the well known Hagen-Poiseuille flow with the well-defined parabolic velocity profile. What happens when the flow is turbulent? The flow is introduced with small vortices (eddies) which allow for mixing of the layers that were following a straight line in the laminar case. This destroys the parabolic profile and we are left with a different curve (which may or may not be a parabola). Moreover, due to this chaotic mixing, if I were to measure the velocity of the flow at one point at one time, I am no longer guaranteed that the velocity will be the same at the point at a different time.

As you can see, the chaos has ruined any sense of understanding one has about pipe flow. No wonder you wouldn’t want to venture around this. But, alas! There is hope. Regardless how chaotic the flow is, it still has to satisfy the Navier-Stokes and Continuity. No flow (in the macroscopic world) can break the Navier-Stokes and Continuity. Further, if you made the measurement of the flow at a point for a very long time, you would observe that the flow is not randomly picking values, but it is in fact fluctuating about a mean value. Thus, we can now bring in statistical analysis and make sense of what is happening in this chaotic world.

For example, if I say that the flow a Gaussian distribution about the mean with a standard deviation of $latex \sigma$, I can give the probability that a flow will have a given velocity. But I can never say with 100% certainty that the flow will have a given velocity. Isn’t this great? Even if my world is so chaotic, I have a way to quantify it mathematically and I can make the necessary deductions from it.

From random walks, to quantum mechanics, to turbulence, we are surrounded by probabilities. Even our beloved deterministic world is just probabilities. Only difference here is that the fluctuations are so small, it is irrelevant for our considerations.